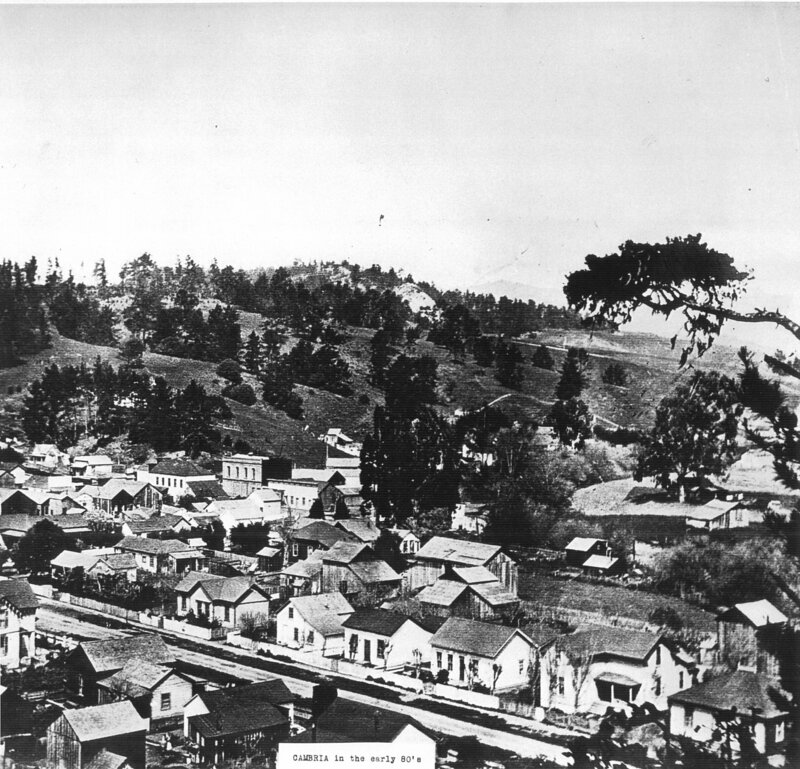

General Early History

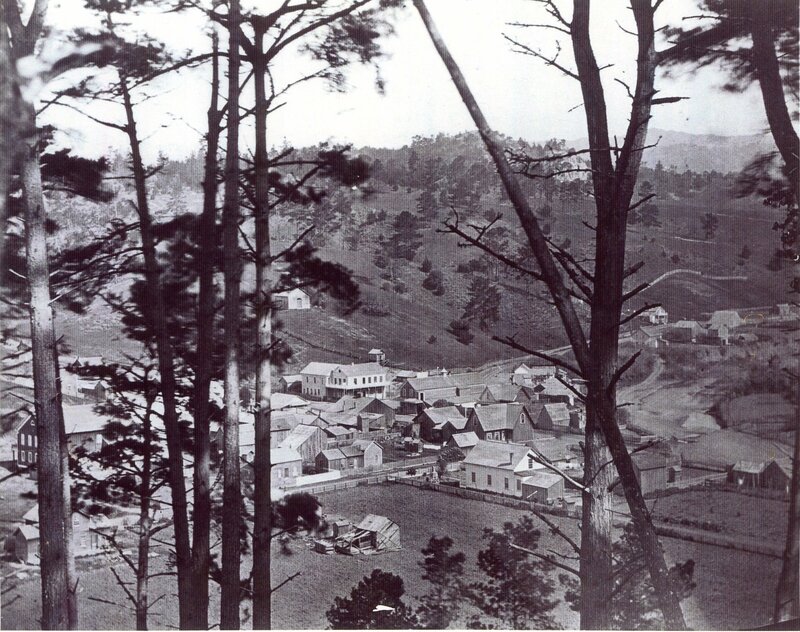

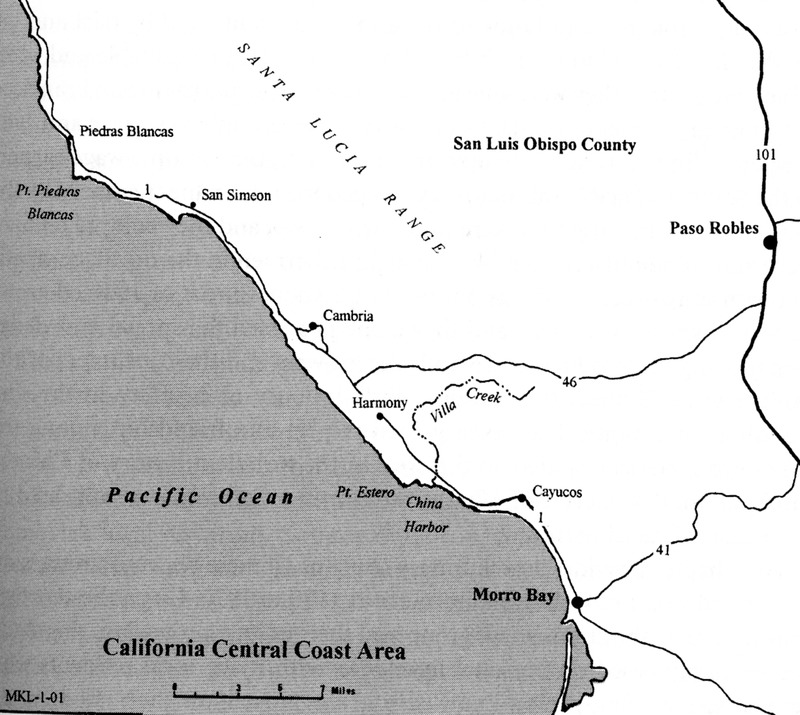

Following the secularization of the California missions in 1833, the land surrounding and including Cambria was granted to Julian Estrada in 1841, and patented to him in 1865. From then on, Cambria grew rapidly due to the presence of several industries. Being close to the coast, the port and eventual wharf brought lots of trade to the area. Stock raising was also a profitable business, but Cambria became largely agricultural during and following the dry years of 1863-1864. The staples of Cambrian agriculture were wheat, barley, hay, beans, and dairy. Later, in 1871, quicksilver was discovered in local mines, encouraging further growth for the city.

Local Chinese History

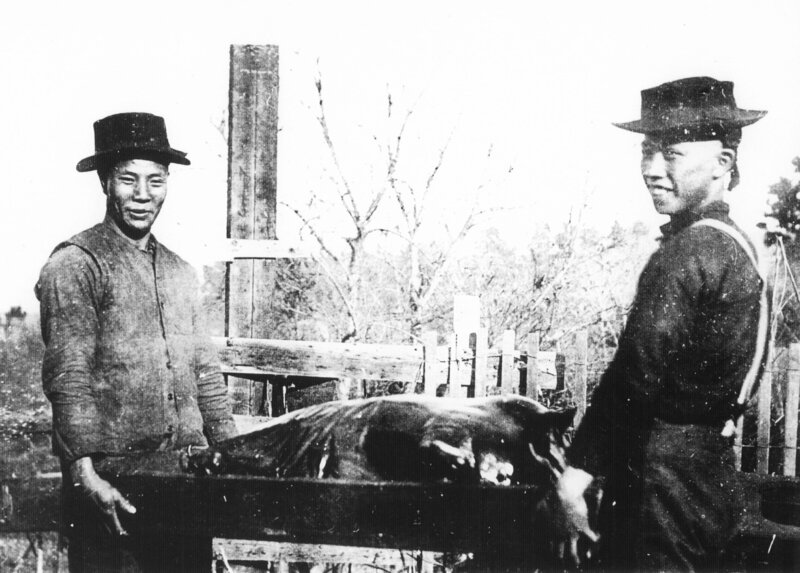

While it is not known when the Chinese came to the Central Coast, the Cambrian census records the presence of Chinese residents beginning in 1870 with thirteen-year-old Sam Su. Upon first arriving, they worked in the general area as miners in the local quicksilver mines, laborers, and gatherers of abalone and seaweed.

Chinese fishermen originally fished along the coast in Monterey County; however, due to hostile Italian and Portuguese fishermen, the Chinese started fishing at night and drifted south, arriving at the towns of San Simeon, Cayucos, and Cambria. Upon arriving at the Central Coast they discovered Ulva, an edible type of seaweed, and began cultivating the seaweed. The process for harvesting Ulva was long and arduous. First, the plant needed to mature for four months and reach the height of eighteen to twenty-four inches before it could be harvested. Once it reached this height, the plant was picked and the leaves were washed to remove all traces of sand. This step was important because if the seaweed contained sand it could not be sold at the market. Next, the seaweed was transported to higher ground to start the weeks-long drying process. Thoroughly drying the seaweed was essential to prevent it from clinging together and spoiling.

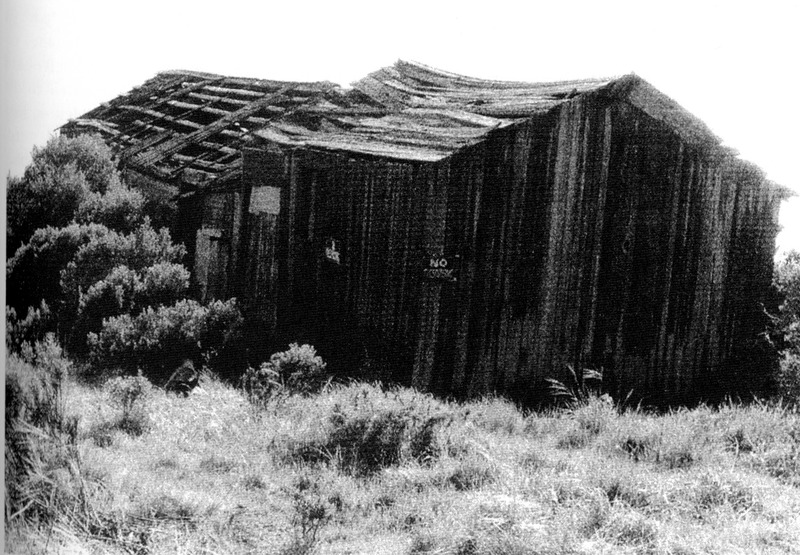

Wong How is a significant figure in the history of Chinese seaweed farming, seeing as he is considered to be the last seaweed farmer. Born in Canton, China in 1895, Wong How and his family moved to San Francisco in 1909, a city of which his father was already a citizen. On the 1939 census, Wong How listed himself as a seaweed farmer living in San Simeon. He did indeed live on the Central Coast in a cabin he built himself, consisting of a core dwelling, a kitchen/workroom, and a section for storage. The placement of his cabin was incredibly strategic, giving him access to the coast where Ulva was plentiful, as well as grassy fields necessary for drying the seaweed.

As shown by Wong How’s prowess in the field, the Chinese were fantastic fishermen. By mastering the environment, gaining proficiency in harvesting and curing their crop, obtaining the ability to transport their goods, and maintaining good business and social relations, Chinese seaweed farmers established an incredibly lucrative business in the United States. When the Chinese were pushed out of the maritime industry they themselves established, seaweed farmers were able to continue their work into the 1900s, seeing as they posed no threat to other laborers due to their unique field of work. As such, these farmers had no competition, and were able to continue their profitable work.

Despite the advantageous nature of the business, seaweed farming seems to have retired along with Wong How when he left both seaweed farming and his China Cove cabin in 1975 and moved to San Francisco, where he died the same year at the age of eighty.

The history of Chinese seaweed gatherers is important to recognize because it highlights how early Chinese settlers were able to pursue their own interests by working in an industry that allowed them to be their own bosses. Although this work was labor intensive, it provided stable employment and enabled them to accumulate wealth during a time period in which anti-Chinese sentiment often prevented Chinese settlers from obtaining jobs that paid high wages.

The Chinese Center

The life of a seaweed gatherer was isolating and provided little opportunity for social contact. Seaweed gatherers would live in cabins that were located four-five miles apart from each other. Driven by their desire to socialize with other people, the Chinese Center in Cambria was constructed. The Chinese Center provided seaweed gatherers with a place to rest and socialize with other seaweed growers and local residents. Located along the Santa Rosa Creek, this area was considered a refuge away from the coast, allowing them the time and space to rest, interact, write letters to home, cook, and practice traditional holidays and events. These celebrations would often last several days, with fifty to sixty community members staying for the duration. Food would be spread out on tables, accessible at all times for people to enjoy various dishes such as pig, chicken, and rice wine. Gambling would go on day and night, and for added fun, the loser had to drink for each loss until they could no longer play and someone else would have to take their place.

This center was not typical of other Chinatowns. Instead of having a stable population of residents, people would stay for short periods of time, ranging from one month, one week, or one day. Only a few community elders came to be considered “permanent” residents of the Chinese Center, such as Lee Bow, Old Sam, and Chinese Mary. Lee Bow was known for gambling, giving Chinese candies to children, and sharing (over-seasoned) pig with neighbors during Chinese festivals and celebrations. Old Sam owned the local laundry, and was subject to practical jokes from local youths. Chinese Mary was fondly remembered as a elderly woman who would act as a mother for young, unmarried men.

On the 1900 census, fifty-four-year-old Que Lee is listed as a fisherwoman and as the head of household. A 1908 death certificate for Ah Que, who also went by Mary Lee, shows her place of death as near Cayucos, the coastal area near Cambria where Chinese fishermen resided. Although it is mostly speculation, Que Lee could be Ah Que, who could be Chinese Mary. Not only do Que Lee and Ah Que share the Que name, but Ah Que’s alternative name was Mary. Furthermore, Que Lee having been listed as the head of household supports the hypothesis that she is the “mother” caring for single men staying in the Chinese Center that Chinese Mary is remembered to be.

The decline of seaweed trade and the loss of these “permanent” residents of the Chinese Center are significant factors as to why the Chinese population in Cambria declined during the 1910s and '20s. Ulva was an important part of the Chinese diet, both for those within the United States and in China. A great deal of the seaweed farmed and cured by the Chinese in Cambria were sent to China; however, when China became Communist in the early 1910s, trade between China and the United States ceased. Without this commercial relationship with China, seaweed farming became nearly obsolete along the coast. As such, many Chinese Cambrians moved to San Francisco, where they found new jobs.

Furthermore, as “permanent” residents like Lee Bow, Old Sam, and Chinese Mary left or passed, the community began to disperse, joining friends and family in San Francisco – thanks to the invention of the automobile – leaving the local structures abandoned by the 1920s.

Interracial Relations in Cambria

Being a permanent resident of the Chinese Center was rare, and most of the residents in the surrounding residential area of Cambria were not Chinese. One such family was the Sotos.

Margaret, Betty, and Lila Soto have been a part of the Cambrian community for generations. Their family history in Cambria begins with their maternal grandfather, Lewis Maggetti, who came from Switzerland to Cambria to work as a cobbler and continued with their mother, Agnes Maggetti, who was born in Cambria. Although their father Joaquin “Jack” Soto was not a native of Cambria, he was a well known member of the Cambrian community and owned a butcher shop that Chinese settlers would frequently visit to buy groceries. As described by Margaret and Lila Soto, their father had a good relationship with the Chinese. He made contributions to Chinese New Year celebrations by butchering the pork for the Chinese. Additionally, their father helped a Chinese fisherman, Ah Fey, who was arrested for fishing undersized abalones. The game warden agreed to let Ah Fey go under the condition that he paid the $50 fine. Unable to pay this fine, Jack Soto helped Ah Fey by paying the fine himself. The next day, a group of Chinese men returned to the home of Jack Soto to pay their bills.

Another prominent non-Chinese family in Cambria are the Warrens, who had resided on the Central Coast since Will and Lily Messic Warren homesteaded ranch land in 1815. Their grandson, Walter Warren, owned property adjoined to the Cambrian quicksilver mine where Walter’s father, Joseph Warren, worked during World War I when mercury was valuable for explosives. Walter had many memories of his father working in the mine alongside up to seventy other men at a time, some of which included Chinese workers. It was with a thousand dollar loan from Joseph that Walter purchased his ranch land on San Simeon Creek.

Forrest Warren, a cousin of Walter Warren and a “fifth-generation Cambrian,” came into ownership of the Chinese Center property in 1916, after a majority of the Chinese population had moved away. The older, less stable buildings were torn down, while the others were moved, as will later be shown by a series of Sanborn maps. It wasn’t until Forrest Warren found an old Chinese coin in one of the buildings that he began researching its historical significance. What he found was that the building, known as the Red House, was the hub of where the Chinese working on the coast came to socialize, as well as a possible Chinese temple.

The Red House

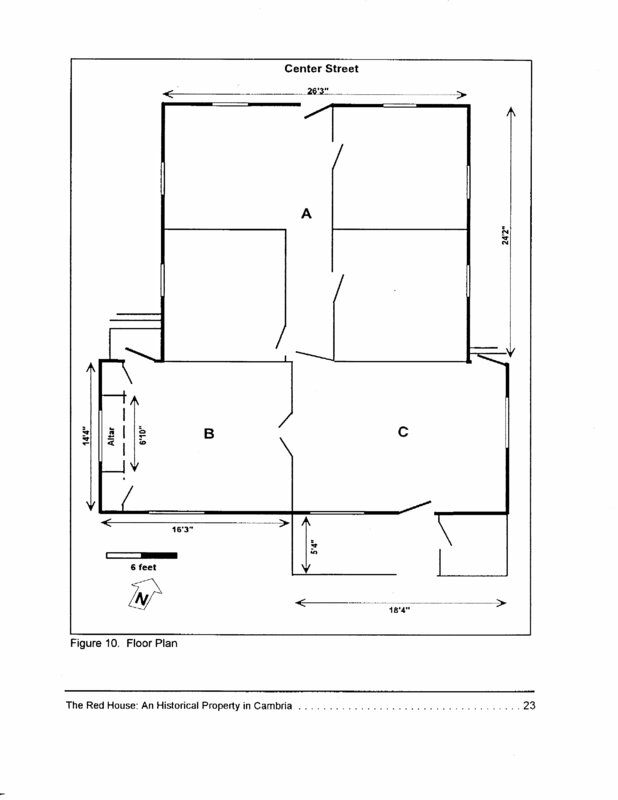

The Red House is made up of three rooms – labeled A, B, and C on the map below. Room A is considered the front entry room, in which the exchanging of news, gambling, and other socializing took place. This room faces Center Street, and would have had walls that were plain other than the names of donors. Room A was most likely built in the early to mid-1890s.

The Chinese Temple

Unlike Room A, Room B would have been expensively decorated. Attached between 1925 and 1926, this section of the Red House is often referred to as a Chinese Temple, because within Room B was a red, gold, and blue altar. With turquoise interior walls and a red interior altar seat, this altar was set up in the simple Tong style and therefore “would have been decorated with two candlesticks, incense bowls, a rectangular bowl, and a pair of vases containing flowers.”

Some have posited that this room acted as a Buddhist temple, but this is unlikely. It is highly probable that Room B existed as a branch of the Chee Kung (also spelled ‘Kong’) Tong, or the Zhigongtang. The Chee Kung were a secret fraternal society that opposed the then-current Manchu government in China and aimed to re-establish the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). In the United States, the Chee Kung also worked to provide needs to Chinese Americans.

There are several aspects of the altar that support its being a Chee Kung Tong branch rather than a Buddhist temple. Other than the aforementioned Tong style of the altar, there was a sign displaying the character Wu, or “military.” This character references Guandi, the God of War, a deity found not in Buddhist temples but among the Chee Kung. As a representation of unity, brotherhood, and the spiritual strength and sacredness of their cause, Guandi was in fact the primary deity of the Chee Kung. Furthermore, “King of Wu, who was the first ruler of the Zhou Dynasty, represents the beginning of the tradition of continuous rule in China,” a fact that correlates to the Chee Kung’s efforts to re-establish the Ming Dynasty.

If the Red House did not serve as a temple nor as a branch of the Chee Kung Tong, it is also highly likely that it simply existed as an informal center for community. Whatever its intended purpose, it was a place for the Chinese population of Cambria to gather, cook, gamble, celebrate, speak in their own language, and socialize with one another.

The third room, Room C, has no clear purpose. Attached either in 1917 or 1919, this room had a sink, a tub, and a porch.

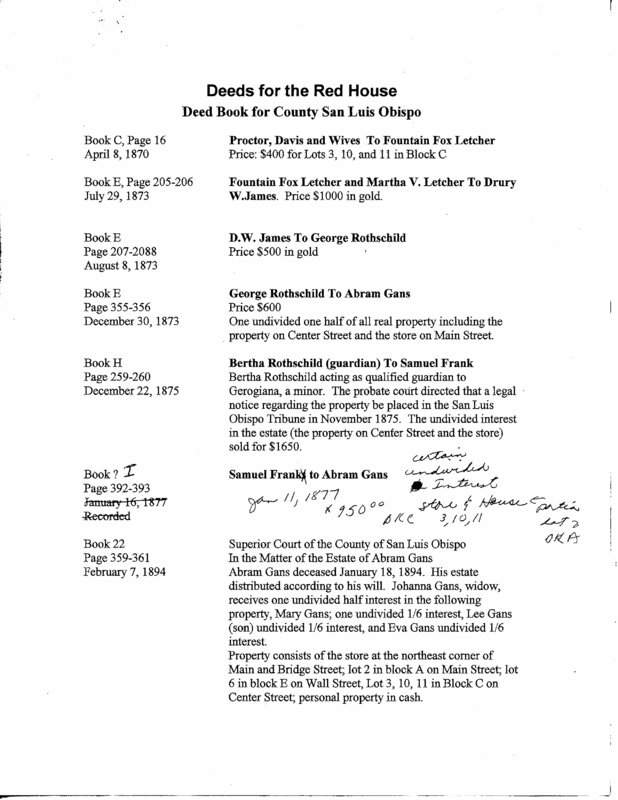

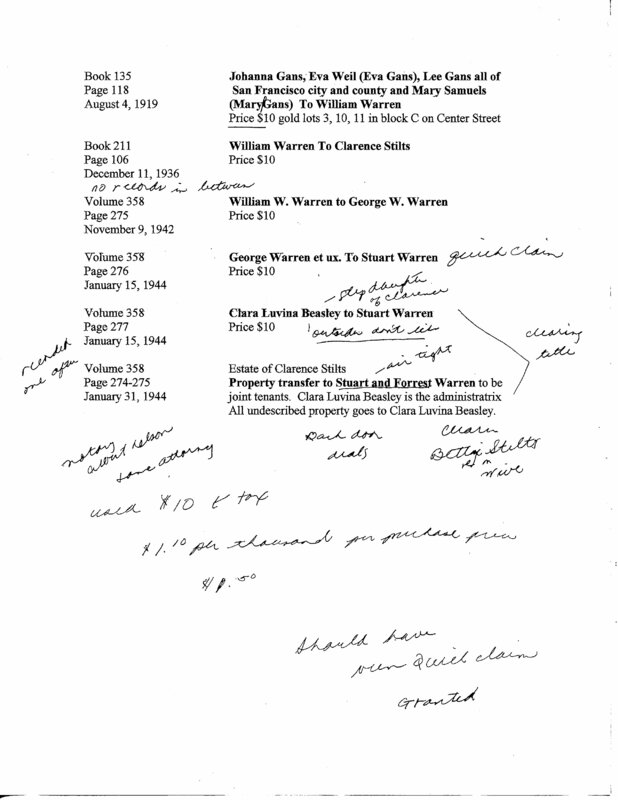

History of Ownership

Ownership of the Chinese Center in Cambria exchanged hands several times for over a century. Listed below are some notable moments within this period, and a more comprehensive scope of ownership of the Red House can be found in the photographs included below.

- April 1870: George W. Proctor (blacksmith), George S. Davis (blacksmith and hotel), and their wives sold Block C, Lots 3, 10, and 11, to Fountain Fox (sawmill)

- August 1919: William Warren purchases the property on Center Street from the Gans Estate. William Warren, his wife Lily, and their children occupy the property on Center Street. Calista Warren, William’s mother, lives on the property as well

- 1925-1926: The Joss House was attached to Red House on Center Street

- January 1944: Forrester Warren and his brother Stuart are named as joint tenants in the property on Center Street by the estate of Clarence Stilts

- The Red House remained vacant for a period of time

- 1953: Forrester Warren and Mary Ellen Millard Warren’s family move into Red House with their children, Forrest and Linda

- 1992: Forrester Warren dies and Linda and Brad Seek inherit property

- 1999: Property sold to Greenspace by Brad Seek after Linda’s death

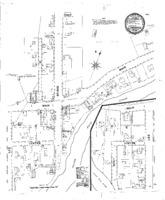

The Chinese Center: 1886-1926

1886

All the way on the left hand side, above the Santa Rosa Creek, there are three buildings labeled “Chinese.” These buildings are most likely the Chinese laundry that the Chinese were allowed to build on the Gans’ land.

1892

In the same location, now only two of the buildings are labeled as “Chinese Laundry.” The third building is simply labeled “Chinese,” which still identifies the building as part of the Chinese Center.

1895

The “Chinese Laundry” remains. The third building, previously labeled “Chinese,” has now been moved further away and labeled as “Chin. Joss House,” first identifying the presence of a Chinese temple on the map.

1913

The “Joss” House has been moved again, and now has a circle behind it. This circle most likely represents the fire pit used to cook pork during festivals and celebrations. Furthermore, two buildings off to the left are labeled as “Chine [sic] Cabins. As recalled by the Soto sisters, Chinese fishermen would stay in cabins when visiting town – it is likely these are those cabins.

1926

The buildings are gone entirely. At this point, the Chinese population of Cambria have moved away, most headed for San Francisco.

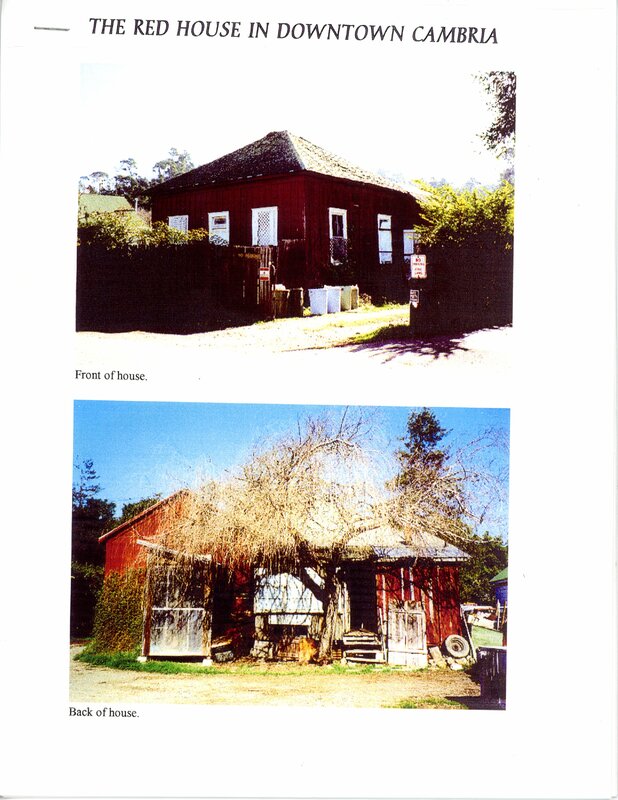

The Red House: Then and Now

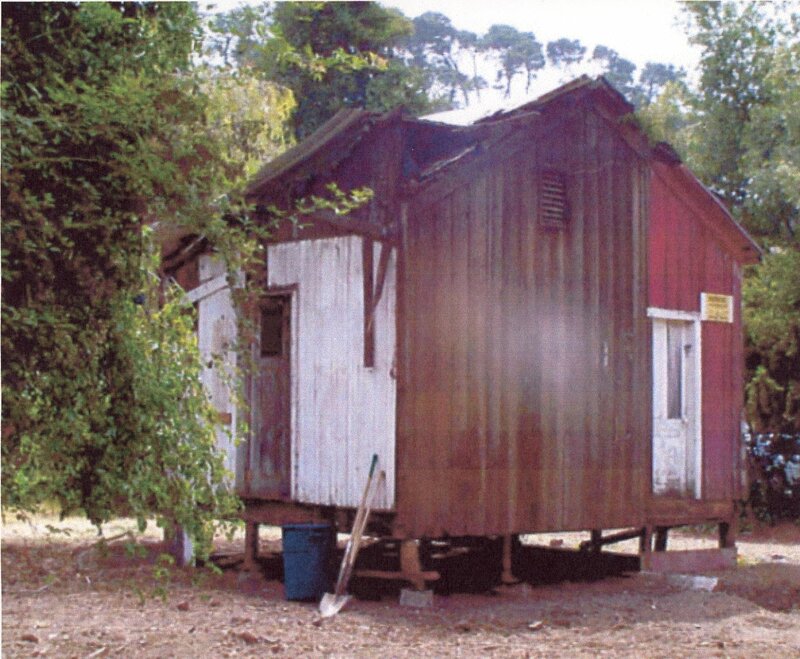

Since coming into ownership of the Red House in 1999, Greenspace renovated the building in an effort to preserve both Chinese American history and one of the few Chinese temples of the Central Coast.

In the photos below, the renovations are evident. Comparing the exterior, a ramp has been added, the architecture slightly altered, and the paint redone. As for the interior, the most evident remodeling has been done in the structure believed to be a Chinese temple. From a boarded up window with faded paint, the altar once again is ornately decorated and surrounded by turquoise painted walls, done in the previously mentioned Tong style.

Significance of the Cambria Collection

As an organization that aims to record, preserve, and communicate the history of Chinese Americans, the Cambria Collection is a valuable source to the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California in that it helps to establish a more complex and complete scope of Chinese American history. This collection inserts into the dominant narrative of United States history a new perspective that is often overlooked, forgotten, or omitted. Records like those provided by the Cambria Collection reassert the role of Chinese Americans in national and local histories and affirms the diversity of such histories. Chinatowns and their landmarks showcase the ways in which Chinese Americans lived and worked. The Chinese Center and the Red House are unique in this regard, seeing as they show the Chinese community in Cambria outside of where they lived and worked. As a place for socializing – cooking, gambling, conversing, sharing news, and celebrating – the Chinese Center offers a glimpse into the ways in which Chinese Americans established and fostered their sense of community. When working to achieve a more holistic history of Chinese Americans and the United States in general, as the CHSSC does, collections like the Cambria Collection are necessary to fill in the gaps and ensure that the stories and voices of those within the gaps are preserved and included.

“Cambria Talk,” Linda Bentz, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

“Chinese temple: Some call it link to Cambria’s past,” Tim Ryan, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

Dolores K. Young, “The Seaweed Gatherers on the Central Coast of California,” in The Chinese in America: A History from Gold Mountain to the New Millennium, ed. Susie Lan Cassel (California: AltaMira Press, 2002), 156-172.

“The Early Chinese” from Where the Highway Ends, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

Greenspace - The Cambria Land Trust, “Cambria's Chinese Temple Designated as Place of Historic Interest,” Greenspace, https://greenspacecambria.org/f/cambrias-chinese-temple-designated-as-place-of-historic-interest.

“Quicksilver!: Mercury Mining On The Central Coast,” Millie Mauer, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

“The Red House: An Historical Property in Cambria,” Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

Roberta S. Greenwood and Dana N. Slawson, “Gathering Insights on Isolation,” Historical Archaeology: The Archaeology of Chinese Immigrant and Chinese American Communities 42, no. 3 (2008): 68-78.

“Soto sisters part of Cambria’s heritage,” Donald Munro, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

“Walter Warren’s life story is tale from the wild west,” Forrest Warren, Cambria Collection, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.